- ECE Home

- Undergraduate Home

- My Home

- Professional Practice Exam

- The Engineering Profession

- History of Common and Statute Law

- Overview of the Professional Engineers Act

- Overview of Ontario Regulation 941

- Code of Ethics

- Professional Misconduct

- Ethics and Misconduct

- Complaints, Discipline, and Enforcement

- Contract Law

- Tort Law

- Significant Cases

- Intellectual Property

- Part A Questions

- Part A Cases

- Part B Definitions

- Part B Cases

- Site Map

- Acknowledgments

Engineering Law and Professional Liability: Case Studies

Updated for 2010 Changes to the Professional Engineers Act

These web pages have been updated to include both enacted and pending changes due to the Open for Business Act, 2010. Note that some changes will not be in force until proclaimed by the Lieutenant Governor; for example, the putting into force the end of the industrial exemption has been delayed numerous times.

Disclaimer

All information on this website is provided without any warranty to its correctness. The material on these pages reflects Douglas Wilhelm Harder's best judgment in light of the information available to him at the time of its preparation. Any use which a third party makes of these pages, on any reliance on or decision to be made based on it, are the responsibility of such third parties. Douglas W. Harder accepts no responsibility for damages, if any, suffered by any third party as a result of decisions made or actions based on these pages.

The second, third, and fourth questions of Part B Engineering Law and Professional Liability have always been case studies. The questions together with references to the appropriate sources in Donald L. Marston's text Law for Professional Engineers, 4th Edition as well as sample answers are provided for the years

April 1993, September 1998, April 1999, August 2000, August 2001, April 2002, December 2004, April 2005, December 2005, December 2006, April 2007, August 2007, December 2007, April 2008, August 2008, December 2008, and April 2009.

Of the questions on these papers, 21 have sample answers and six are yet to be answered. The six include April 1993 Question 2, April 1993 Question 3, April 1993 Question 5, September 1998 Question 4, and September 1998 Question 5 and one below.

I would like to thank Hugh Jack for having typed in Questions 23-35 (available at Egnineer-on-a-Disk) and allowing me to copy them here.

- HESI v. ERRS

- Owner v. Mammoth, Swift, et al.

- Ontario Human Rights Code

- Employer v. Former Employee

- optionee v. optionor

- BIDCO v. large engineering firm

- Pulverized v. Clearwater

- NEWCO v. large engineering firm

- NATIONAL v. architect et al.

- manufacturing company v. engineering firm

- Owner v. XYZ Construction Inc.

- large accounting firm v. ABC Hardware

- Paperco v. Manuco

- municipality v. engineering firm

- Light Rail Inc. v. Ever Works, Ltd.

- owner v. architect et al.

- Pulpco v. industrial contractor

- telecommunications development company v. contractor

- information technology firm v. structural engineering firm

- consultant v. politician

- XYZ Ltd. v. E Inc.

- ACE v. IMCO

- Red Fire Mines Ltd. v. Superclean Ltd.

- owner v. contractor

- Unjammers Inc. v. Acme Manufacturing et al.

- Skylift Inc. v. Jason Smith

- owner v. Regina et al.

- contract questions

- owner v. engineering firm

- owner v. contractor

- Office Tower Owner v. architect et al.

- New Shopping Centre Owner v. engineer

- Municipality v. Jason Sharp et al.

- Rocky Rail Ltd. v. TEDI

- Office Tower Owner v. architect et al.

Case 1

Hyper Eutetoid Steal Inc. ("HESI") is a company which produces various types of style for industrial applications. In order to increase the strength of its steel products, HESI uses a process of quenching and tempering.

During the quenching stage, hot steel is quickly cooled with water. During the tempering phase, the steel is then heat treated for an appropriate time. The process requires large amounts of water and heat.

Faced with rising costs for energy, HESI decides to install a heat recovery system. The system would include a heat exchanger by which heat could be recovered from the cooling water in the quenching stage, combined with additional heat from a steam line in the plant that was otherwise not being fully utilized. The recovery heat, then, would be used to heat the steel in the tempering stage.

HESI entered into an equipment supply contract with Energy Recovery and Recycling Systems Inc. ("ERRS"). ERRS agreed to design, supply and install a heat recovery unit for a contract price of $600 000. After an analysis of HESI's process, ERRS determined and guaranteed in the contract that the heat recovery system would recover 40% of the heat in the cooling water and that this would result in substantial savings in energy costs.

The contract also contained a provision limiting ERRS's total liability to $600 000 for any loss, damage or injury resulting from ERRS's performance and its services under the contract.

The heat recover system was installed and operation; however, certain defects in the heat exchanger prevented the system from recovering more than 5% of the heat in the cooling water. After repeated unsuccessful attempts by ERRS to remedy the defects, HESI hired another supplier, who, for an additional $800 000 replaced the heat exchanger and was able to achieve the level of performance originally promised by ERRS. The total amount received by ERRS under its contract was $500 000.

Explain and discuss what contract law claim HESI can make against ERRS in the circumstances. In answering, please include a brief summary of the development of relevant case precedents relating to the enforceability of contract provisions that limit liability.

Relevant case law includes the concept of fundamental breach with Harbutt's Plasticine Ltd. v. Wayne Tank and Pump Co. Ltd. where the defendant used "thoroughly" and "wholly" unsuitable for is purpose. The concept of fundamental breach has not been overruled; however, in the case of Hunter Engineering Company Inc. v. Syncrude Canada Ltd., the decision was to accept the freedom of contract and true "construction approach". In this case, the heat exchanger did recover at 5% of the heat in the cooling water and it would be unlikely that the concept of a fundamental breach would be applicable here and therefore the limitation clause would be enforced.

New: In Tercon Contractors Ltd. v. The Queen in right of British Columbia, the Supreme Court of Canada stated that "With respect to the appropriate framework of analysis the doctrine of fundamental breach should be 'laid to rest'."

In this case, through its performance, ERRS breached its contract with HESI and therefore HESI may repudiated the contract by the breach and seek another party to fulfill the contract and may also begin an action to claim for those direct damages. (This is based on my understanding that the heat recovery is a condition of the contract and not a warranty.) ERRS may be able to demonstrate that additional work has been performed and may be paid quantum meruit for such work; however, no evidence of such work is given in the case.

Therefore, HESI may claim $600 000 in direct damages however, it must absorb the $100 000 difference between the original contract amount of $600 000 and the total cost of $700 000 once damages by ERRS are paid. ERRS may still be able to claim quantum meruit for at least part of the $100 000 difference between what it was paid and the monetary benefits stated in the contract.

Case 2

Mammoth Undertaking Ltd. ("Mammoth"), a development company, retain an architectural firm to design a twenty-storey office building. The architect also agreed with Mammoth that the architect would provide or arrange for inspection services during the course of the construction of the project in order to ensure that construction was carried out in accordance with the project plans and specifications.

The architect prepared a conceptual design and retained a structural engineering firm to prepare the detailed structural design for the project and also to carry out the inspection services to ensure that all structural aspects of the construction of the project were carried out in accordance with the project plans and specifications.

The engineering firm prepared the structural design and eventually Mammoth awarded the contract for the construction of the project to a general contractor, Swift Construction Ltd. ("Swift").

The engineering firm appointed one of its employee engineers, Jim Neophyte, a recent engineering graduate, as the engineering firm's representative and inspector on the construction site.

Construction commenced during the month of October and soon thereafter Swift recommended to Mammoth that a substantial cost savings could be achieved if the specified fill material around the foundation was changed to a more readily available material. Mammoth sought the architect's advice on the suitability of the proposed alternative fill material and indicated to the architect that it was most important that a decision be made as soon as possible in order to complete as much of the foundation and back-filling as possible prior to frost conditions setting in.

The architect, in turn, referred the matter to the structural engineering firm through its representative Jim Neophyte, requesting that the structural engineering firm approve the proposed changes as quickly as possible in the circumstances. Jim Neophyte determined that the original fill material had been specified by an engineer who no longer worked for the structural engineering firm and that the specification had been made on the basis of a careful investigation of soil conditions at the site. Jim Neophyte contacted on of the structural engineering firm's vice-presidents as was authorized to advise the architect as to the suitability of the alternative fill material after conducting an appropriate investigation.

Under significant pressure from both Mammoth and Swift to approve the proposed fill material without delaying the construction schedule, Jim Neophyte approved the change of materials without giving due consideration to the possible repercussions.

The substitute material did not drain as well as the material originally specified; in fact, it retained some water and, as it expanded during freeze up, it caused significant cracking in the foundation walls, necessitating remedial work resulting in substantial additional expense being incurred by Mammoth. In addition, the completion of the project was considerably delayed as a result.

Explain the potential liabilities in tort law arising from the preceding set of facts. In your explanation, discuss and apply the principles of tort law and indicate a likely outcome of the matter.

To demonstrate liability in tort, one must demonstrate that

- the defendant owed the plaintiff a duty of care,

- the defendant breached that duty by his or her conduct, and

- the defendant's conduct caused the injury to the plaintiff.

The purpose of tort law is to compensate the injured party for the damages and not to punish the tortfeasor.

Reference: Marston, p.39.

The professional engineer is expected to apply reasonable care and prudence in the practice of professional engineering and thereby owes a duty of care to the development company even if no contractual relationship exists between the two.

The professional engineer Jim Neophyte negligently approved the alternative fill material. The general contractor Swift was negligent in proposing an alternative fill material on the basis of availability and not suitability.

The structural engineering firm is vicariously liable for the actions of its employees and therefore the firm must take responsibility for the negligence of its employee.

The injuries sustained by Mammoth include the costs of the remedial work as well as the delay of the project. In considering the costs due to delays in the project, however, it would be necessary to determine if any liquidated damages were specified in any of the contracts.

Case 3

(a) The Ontario Human Rights Code protects employees against certain types of behaviour in the workplace. Briefly identify (list) five examples of inappropriate conduct in the workplace that are prohibited by the Ontario Human Rights Code.

Reference: Ontario Human Rights Code, Part 1.

Harassment in employment

5. (2) Every person who is an employee has a right to freedom from harassment in

the workplace by the employer or agent of the employer or by another employee because of

race, ancestry, place of origin, colour, ethnic origin, citizenship, creed, age,

record of offences, marital status, family status or disability.

Harassment because of sex in workplaces

7. (2) Every person who is an employee has a right to freedom from harassment in the workplace because of sex by his or her employer or agent of the employer or by another employee.

(b) Engineers, as creative professionals, may require intellectual property protection. Briefly identify three types of intellectual property protection and the duration of protection provided by each.

Reference: Marston, Ch. 23, Intellectual Property, pp.281-293.

| Class | Term |

|---|---|

| Patents of Invention | 20 years |

| Trade-marks | 15 years with unlimited 15-year renewals |

| Copyright | 50 years after the death of the author |

| Industrial Design | 10 years |

(c) In some construction contracts, an engineer is authorized to be the sole judge of performance of work by the contractor. Where such a provision is stated, is it possible that the provision will not be enforceable on account of the manner in which the engineer performs his or her duties? Explain.

Reference: Marston, Ch. 24, Construction Contracts, pp.181-184.

The engineer is required to act judicially and therefore act independent of the owner and in good faith. So long as the engineer maintains this standard, the engineer's decisions will be binding upon the parties.

However, if the engineer acts with fraudulent intent, in bad faith, or otherwise willfully disregards his or her duty, it is likely that in an action, the courts would not consider the decisions to be conclusive and binding.

(d) The question of how long an engineer or a contractor can be sued for negligence or breach of contract is one that is of concern to professional engineers and to contractors. Describe the limitations periods during which engineers and contractors can be sued in tort and in contract.

Reference: Marston, Ch. 5, Limitation Periods, pp.71-76.

The Limitations Act, 2002, provides for an ultimate fifteen-year limitation period beyond which no actions in tort or for breach of contract. The Act also provides for a two-year limitation period both in tort and for breach of contract starting from when the injured party "discovered or ought reasonably to have been discovered the damage".

The concept of discoverability was confirmed by the Supreme Court of Canada case City of Kamloops v. Nielsen et al., p.72 (also see LexUM and wikipedia).

Case 4

A professional engineer entered into a written employment contract with a Toronto-based civil-engineering design firm. The engineer's contract of employment stated that, for a period of five years after the termination of employment, the engineer would not practice professional engineering either alone, or in conjunction with, or as an employee, agent, principal, or shareholder of an engineering firm anywhere within the City of Toronto.

During the engineer's employment with the design firm, the engineer dealt directly with many of the firm's clients. The engineer became extremely skilled in preparing cost estimates, and established a good personal reputation within the City of Toronto.

The engineer terminated the employment with the consulting firm after three years, and immediately set up an engineering firm in another part of the City of Toronto. The engineer's previous employers then commenced a court action for an injunction, claiming that the engineer had breached the employment contract and should not be permitted to practice within the city limits.

Do you think th engineer's former employers should succeed in an action against the engineer? In answering, state the principles a court would apply in arriving at a decision.

TBW.

Case 5

A mining contractor signed an option contract with a land owner which provided that if the mining contractor (the "optionee") performed a specified minimum amount of exploration services on the property of the owner (the "optionor") within a nine-month period, then the optionee would be entitled to exercise its option to acquire certain mining claims from the optionor.

Before the expiry of the nine-month "option period", the optionee realized that it couldn't fulfill its obligation to expend the required minimum amount by the expiry date. The optionee notified the optionor of its problem prior to expiry of the option period and the optionor indicated that the option period would be extended. However, no written record of this extension was made, nor did the optionor receive anything from the optionee in return for the extension.

The optionee the proceeded to perform the services and to finally expend the specified minimum amount during the extension period. However, when the optionee attempted to exercise its option to acquire the mining claims the optionor took the position that, on the basis of the strict wording of the signed contract, the optionee had not met its contractual obligations. The optionor refused to grant the mining claims to the optionee.

Was the optionor entitled to deny the optionee's exercise of the option? Identify the contract law principles that apply, and explain the basis of such principles and how they apply, to the position taken by the optionor and the optionee.

This case is similar to that of Conwest Exploration Co. Ltd. et al. v. Letain where the optionee had to take certain steps by a specific date limit.

In this case, the optionee received a verbal agreement from the optionor that the option period would be extended. Because the verbal agreement was not associated with any form of consideration, it is a gratuitous promise. If it can be established that such a promise was made then the by the above case, the courts would equitably estop the optionor from reverting to the strict contractual rights.

From the wording of the case, it would appear that the optionee was required to perform additional exploration beyond they nine-month period and was only obligated to perform a certain amount of exploration in order to exercise the option. Consequently, any additional performance after the limit date of the option would still be part of the original performance expected from the contract and therefore could not be used to demonstrate that such a promise was made.

In the case of Conwest, it appears that one of the requirements was incorporation by a certain date and there would have been no point in pursuing incorporation after the limit date had the gratuitous promise not been made. [Note, if someone is more familiar with the case linked below, please let me know if this interpretation is correct.]

It would be prudent, therefore, that the optionee make some sort of written follow-up with the optionor to determine whether or not the optionor intends to follow through with the gratuitous promise.

Case: Conwest Exploration Co. Ltd. et al. v. Letain, Marston, p.92 (also see LexUM).

Case 6

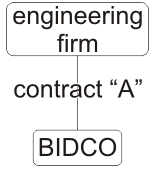

(a)An information technology hardware supplier ("BIDCO") submitted a fixed price bid on a major computer installation project for a large engineering firm, in response to the engineering firm's request for proposals. BIDCO included with its tender, as required, a certified cheque for $100 000 payable to the engineering firm as a tender deposit.

The request for proposal also provided that if the tender was accepted by the engineering firm and the successful bidder did not execute the contract enclosed with the request for the proposal the engineering firm would be entitled to retain the tender deposit for its own use and to accept any other tender.

BIDCO made a clerical error in compiling its tender submission, omitting an amount of $1 000 000 form its tender price of $6 000 000. BIDCO drew the clerical error to the attention of the engineering firm within five minutes after the official time for submitting bids had expired. BIDCO indicated that it wished to withdraw its tender but the engineering firm refused to allow it to do so and awarded the supply contract to BIDCO.

Was BIDCO entitled to withdraw its bid?

The company BIDCO had entered into a bid contract, also known as "Contract A", with the engineering firm. As BIDCO had entered into the contract without actual consideration, it should have been required to seal the bid to demonstrate consideration.

If the seal was placed on the bid, this means the bid contract may be enforced and consequently, BIDCO would not be at liberty to withdraw the bid without breach of contract, the remedy for which is specified in the bid contract as forfeiture of the deposit.

If the bid was not sealed, no contract exists and by Belle River Community Arena Inc. v. W.J.C. Kaufmann Co. et al., no contract exists and therefore BIDCO would be entitled to withdraw.

Was the engineering firm entitled to keep the tender deposit?

If the bid was sealed, yes, otherwise, no.

If ENGCO's report contains negligent misstatements, could a third party who had subsequently purchased land from OWNERCO succeed in a tort claim against ENGCO? Explain.

To demonstrate liability in tort, one must demonstrate that

- the defendant owed the plaintiff a duty of care,

- the defendant breached that duty by his or her conduct, and

- the defendant's conduct caused the injury to the plaintiff.

The purpose of tort law is to compensate the injured party for the damages and not to punish the tortfeasor.

Reference: Marston, p.39.

In Hedley Bryne & Co. Ltd. v. Heller & Partners Ltd., the defendant made a statement which was made which may reasonably be said to be a fraudulent misrepresentation either made knowingly, without belief in its truth, or recklessly. In this case, by giving a response to the plaintiff, the defendant was liable in tort to the plaintiff, the defendant had negligently misrepresented the case, and the conduct lead to the plaintiff entering into a contract with another party. The court concluded that the defendant did have a duty of care to the plaintiff and had it not been for a disclaimer of "without responsibility", the the defendant would have been liable in tort to plaintiff.

Even more similar is the 1994 case Wolverine Tube (Canada) Inc. v. Noranda Metal Industries Ltd. et al.. This case is exceptionally similar to the case presented here where a disclaimer on an environmental compliance audit. Here, the defendant had "the right of the issue of the statement to disclaim any assumption of a duty of care..." and this case is no different. Thus, in this case, as with Wolverine, there was no duty of care on the part of the defendant and therefore the plaintiff cannot claim liability in tort.

In both Bryne v. Heller and Wolverine v. Noranda, had the appropriate disclaimer not been made, the judges clearly stated that the defendant would have been found liable in tort and there is no reason to suspect anything else in this case.

In this similar case, a tort claim against ENGCO could not succeed.

Case 7

Clearwater Ltd. ("Clearwater"), a process-design and and manufacturing company, entered into an equipment-supply contract with Pulverized Pulp Ltd. Clearwater agreed to design, supply, and install a cleaning system at Pulverized Pulp's Ontario mill for a contract price of $800 000. The specifications for the cleaning system stated that the equipment was to remove 99 % of certain prescribed chemicals from the mill's liquid effluent in order to comply with the requirements of the environmental control authorities. However, the contract clearly provided that Clearwater accepted on responsibility what-so-ever for any indirect or consequential damages, arsing as a result of its performance of the contract.

The cleaning system installed by Clearwater did not meet the specifications, but this was to determined until after Clearwater had been paid $720 000 by Pulverized Pulp. In fact, only 70%nbsp;% of the prescribed chemicals were removed from the effluent.

As a result, Pulverized Pulp was fined $60 000 and was shut down by the environmental control authorities. Clearwater made several attempts to remedy the situation by altering the process and cleaning equipment, but without success.

Pulverized Pulp eventually contracted with another equipment supplier. For an additional cost of $950 000, the second supplier successfully redesigned and installed remedial process equipment that cleaned the effluent to the satisfaction of the environmental authorities, in accordance with the original contract specifications between Clearwater and Pulverized Pulp.

Explain and discuss what claim Pulverized Pulp Ltd. can make against Clearwater Ltd. in the circumstances. In answering, explain the approach taken by Canadian courts with respect to contracts that limit liability and include a brief summary of the development of relevant case precedents.

Relevant case law includes the concept of fundamental breach with Harbutt's Plasticine Ltd. v. Wayne Tank and Pump Co. Ltd. where the defendant used "thoroughly" and "wholly" unsuitable for is purpose. The concept of fundamental breach has not been overruled; however, in the case of Hunter Engineering Company Inc. v. Syncrude Canada Ltd., the decision was to accept the freedom of contract and true "construction approach". In this case, the cleaning system did remove at least 70% of the chemicals and it would be exceptionally unlikely that the concept of a fundamental breach would be applicable here and therefore the limitation clause would be enforced.

New: In Tercon Contractors Ltd. v. The Queen in right of British Columbia, the Supreme Court of Canada stated that "With respect to the appropriate framework of analysis the doctrine of fundamental breach should be 'laid to rest'."

In this case, the contract contained a limitation clause that stated that Clearwater accepted no responsibility for indirect or consequential damages. The resulting fine and loss of profits due to the shut down are consequential to the actions of filling the contract and therefore the $60 000 fine and loss of profits must therefore be absorbed by Pulverized Pulp Ltd.

However, Clearwater installed a system which did not meet the requirements of the contract. The specification was that 98% of certain chemicals should be removed from the liquid effluent. The installed system did not meet the specification, and therefore, by its performance, Clearwater is in breach of a condition of the contract. Therefore, Pulverized Pulp may repudiated the contract by the breach and seek another party to fulfill the contract and may also begin an action to claim for those direct damages. (This is based on my understanding that the cleaning requirement is a condition of the contract and not a warranty.) Clearwater may be able to demonstrate that additional work has been performed and may be paid quantum meruit for such work; however, no evidence of such work is given in the case.

Therefore, Pulverized Pulp may claim $950 000 in direct damages but may not claim any indirect or consequential damages amounting to the $60 000 fine and lost profits when the plant was shut down. Clearwater may be able to claim quantum meruit for at least part of the $80 000 difference between what it was paid and the monetary benefits stated in the contract.

Case 8

A newly formed energy company ("NEWCO") decided to investigate the possiblity of developing a liquefaction process to convert coal deposits into oil.

NEWCO entered into a contract with a large engineering firm pursuant to which the engineering firm was to carry out a feasibility study to determine, over a period of eight months and by a specified date, the feasibility of the proposed liquefaction process. The contract between NEWCO and the engineering firm expressly provided that should the feasibility study be completed by the deadline date specified and should the results of the study indicate that the liquefaction process proposed by the engineering firm would meet the specified quality and volumes of liquefied oil output, then the engineering firm would be authorized to carry out further work to develop the liquefaction process to operate on a commercial basis, all on terms and conditions clearly set out in the contract between NEWCO and the engineering firm.

The engineering firm undertook the feasibility study and, although the results of the feasibility study appeared promising and in compliance with the parameters specified in the contract with NEWCO, the engineering firm found that it would be unable to complete the feasibility study by the date specified. The president of the engineering firm explained to the president of NEWCO that the engineering firm would not be able to fulfill all aspects of the feasibility study as required by the specified date. The president of the engineering firm emphasized that whereas the engineering firm would likely be two weeks late in completing its feasibility study obligations, the result of the feasibility study indicated that the liquefaction process would very likely meet NEWCO's requirements for commercial production as specified.

The president of NEWCO indicated to the president of the engineering firm, verbally, that the time for completion of the feasibility study would be extended.

The engineering firm completed the feasibility within two weeks after the date specified in the contract.

Subsequently, NEWCO took the position that the engineering firm had not completed the feasibility study in time and, accordingly, that NEWCO was not obligated under the wording of the contract to authorize the engineering firm to carry out further work to develop the liquefaction process on a commercial basis. Instead, NEWCO issued a request for proposals from several firms for the development of the liquefaction process to operate on a commercial basis. NEWCO selected another firm that was prepared to undertake the development of the process for a fee substantially lower than the fee that was to have been paid to the original engineering firm had it completed the feasibility study by the date specified in the contract.

Actions taken:

- NEWCO has a contract with a large engineering firm for a feasibility study with a deadline date which, if achieved, would give LargeEng an option.

- The engineering firm indicated that the deadline could not be met.

- The president of NEWCO gave a gratuitous promise that the deadline would be extended.

Was NEWCO entitled to deny the engineering firm's right to develop the liquefaction process to operate on a commercial basis? Identify the contract law principles that apply, and explain the basis of such principles and how they may apply to the positions taken by NEWCO and by the engineering firm.

A gratuitous promise is an agreement made without consideration and does not constitute a contract and in this case, it would be a verbal agreement to amend the terms of the already existing contract.

This is a question of equitability. The engineering firm, had it known the deadline was not flexible would not have devoted an additional two weeks of effort finish the study. Because the president of NEWCO gave a gratuitous promise, the engineering firm continued the effort to demonstrate that the process could achieve the required qualities and quantities of liquefied oil.

An agreement made before the signing of the contract but which is not written into the contract will, by the parol evidence rule, will not give cause to the courts to order an amendment to the contract unless it can be shown to be either a common mistake and that the contract is subsequently inconsistent.

After the signing of the contract, however, in the understanding of the nature of human interactions, it is necessary for the courts to prevent the actions or inactions of one party causing the other party to breach the contract. In a case such as John Burrows Ltd. v. Subsurface Surveys Ltd. et al., it was a sequence of late payments which were accepted without an insistence that the the contract was breached; XXX.

In such a case, the court may estop one party from enforcing the strict interpretation of the contract which falls under the remedy equitable estoppel.

If a second contract has already been signed by NEWCO, I am not aware of which remedy the courts would take in this case: either the courts could potentially require that NEWCO pay damages for lost profits or the second contract could be declared illegal in which case the second firm may, too, sue for damages due to misrepresentation.

Case 9

National Stores Inc. ("NATIONAL"), the owner of a grocery store chain in Ontario, contracted with an architect to design and prepare the construction documentation for a new store in a town in northern Ontario.

The architect produced some general construction specifications that included a requirement that an automatic sprinkler system, conforming to the National Fire Protection Association ("NFPA") standards, be installed.

The architect retained an engineering firm pursuant to a separate agreement to which NATIONAL was not a party. Under the contract the engineering form was to prepare the detailed engineering design for the project, including the sprinkler system. The engineering design was to conform to the architect's general specifications.

A recent engineering graduate employed by the engineering firm prepared the design of the sprinkler system. Not being familiar with the NFPA requirements, the employee read certain sections of the standards but did not have enough time, given other project responsibilities, to pay close attention to all the details. A professional engineer reviewed the employee's completed sprinkler system design. Although the professional engineer did not perform a detailed check, the professional engineer considered the design satisfactory.

Six moths after the store opened for business, a fire occurred early one morning. The fire caused substantial damage to the store and to its inventory and NATIONAL had to close the store for repair.

NATIONAL retained a consulting engineer to conduct an independent investigation. The consulting engineer determined that the sprinkler system was inadequately designed. Specifically, the design did not conform to the NFPA standards, which required, among other things, that the coverage per sprinkler head was not to exceed ten square metres. The engineer determined that 10 % of the sprinkler heads were designed to cover an area as high as twenty-five square metres. The report indicated that, in the engineer's expert opinion, had the sprinkler head spacing conformed to the NFPA standards, the fire should have been quickly extinguished and would not have spread to any great extent.

What liabilities in tort law may arise in this case? In your answer, explain the purpose of tort law and identify what essential principles of tort law are relevant. Apply each principle to the facts. Indicate a likely outcome in the matter.

To demonstrate liability in tort, one must demonstrate that

- the defendant owed the plaintiff a duty of care,

- the defendant breached that duty by his or her conduct, and

- the defendant's conduct caused the injury to the plaintiff.

The purpose of tort law is to compensate the injured party for the damages and not to punish the tortfeasor.

Reference: Marston, p.39.

An example of conduct which is often associated with conduct which may result in a tort action is negligence.

This is a case of the unintentional tort of negligence on the part of the professional engineer who approved the sprinkler system designed by one of the engineering graduates. The recent engineering graduate did not properly read the standards and this omission in the carrying out of the work of a practitioner would likely constitute a failure to maintain the standards that a reasonable and prudent practitioner would maintain in the circumstances. As the engineering graduate's work was not thoroughly checked by his supervising professional engineer, he too is liable for the negligent action.

The firm NATIONAL had a contract with the architect and therefore did not have a direct relationship with the engineering firm; however, it is clear that the engineering firm did owe an expectation of care to NATIONAL.

Because the engineering firm is vicariously liable for the actions of the engineering student, NATIONAL would be limited to starting an action for damages in tort against both the architect who was expected to ensure the quality of the work and the engineering firm. This author will not attempt to guess how the courts would divide the damages between the architect and the engineering firm; however, it is unlikely that either one will be given 100% liability.

The purpose of tort law is to compensate the innocent party for injuries which in this case may include the damage to the store, lost inventory, and lost profits.

In this case, it is unreasonable to expect that the damage (the poor design) would have been detected before the fire and therefore NATIONAL would have two further years to start an action against the architect and the engineering firm.

Case 10

A manufacturing company retained an architect to design a new plant. The manufacturer, as client, and the architect entered into a written client/architect agreement in connection with the project. The purpose of the plant construction was to enable the client to expand its manufacturing and warehousing facilities.

The structural design of the plant was prepared by an engineering firm which was retained by the architect. A separate agreement was entered into between the architect and the engineering firm to which the client was not a party.

The engineering firm turned the matter over to one of its employees, a professional engineer with experience in structural steel design who proceeded to complete the structural design of the plant. The client had informed the architect that the second floor of the plant was to be used for manufacturing and warehousing purposes and that forklift trucks would be extensively used in both the manufacturing and warehousing sections on the second floor. The architect passed this information on to the engineering firm. The employee engineer designed a steel frame and specified that the second floor was to be a concrete-steel composite, containing essentially of concrete poured onto a steel deck, and containing a light steel mesh. The steel deck, concrete thickness, and steel mesh specifications were specified in the engineer's design and were taken from design tables which the engineer located in his firm's library and which had been published by a company which manufactured and supplied the steel deck.

The construction of the plant was completed and shortly after manufacturing commenced at the plant, severe cracks appeared in the concrete on the second floor. After two months of operations, the floor cracked and broke up so badly that the plant had to be shut down and a remedial floor slab, heavily reinforced with reinforcing bar, was poured on top of the damaged second floor.

The design of the remedial floor slab was carried out by another consulting engineering firm. After completing its investigation of the cause of the failure of the second floor, the second engineering firm stated that, it its opinion, the engineer who had designed the second floor had sued design tables from the steel deck manufacturer which were 12 years out of date and had also failed to sue the tables that the engineer obviously ought to have used knowing that the floor was intended for manufacturing and forklift truck loading. The second consulting engineering firm concluded that the depth of concrete and size of steel mesh in the floor as initially designed resulted in a floor that might have been appropriate for the design of an office or apartment building but not for manufacturing and warehousing purposes.

What potential liabilities in tort law arise from the preceding set of facts? In your answer, state the essential principles applicable in a tort action and apply these principles to the facts. Indicate a likely outcome of the matter.

This is, in some respects, similar to the case Dominion Chain Co. Ltd. v. Eastern Construction Co. Ltd. et al.. In this referenced case, the plaintiff sought damages for both breach of contract and for negligence (a liability in tort). For liability in tort, one must demonstrate that

- the defendant owed the plaintiff a duty of care,

- the defendant breached that duty by his or her conduct, and

- the defendant's conduct caused the injury to the plaintiff.

The purpose of tort law is to compensate the injured party for the damages and not to punish the tortfeasor.

Reference: Marston, p.39.

In this case, the engineering firm has entered into a contract with an architect to provide the structural design of the plant and therefore had a duty of care to the manufacturing company as the engineering firm is providing services within the practice of professional engineering and therefore the professional engineer is required to not be negligent in providing services and it would appear that by using out-of-date design tables and simultaneously used tables which were inappropriate for the intended use of the floor. If these are the facts, the engineer is therefore almost certainly negligent and guilty of professional misconduct.

By acting negligently and by vicarious liability, the engineering firm therefore breached the duty of care owed to the manufacturing company.

The damages include the loss of income due to the plant shut-down and the cost of the remedial floor slab.

The architect may also be liable in tort as the architect retained this engineering firm and therefore the architect and the engineering firms are concurrent tortfeasors.

Another party which is not mentioned in the case is the contractor who built the floor. One would suspect that the contractor would be aware of current construction practice and should be aware of the purpose of the floor. In such a case, it may be negligent on the part of the contractor to build the floor as stated in the structural design without objection. In this case, the contractor may also be a concurrent tortfeasor.

Therefore, it is likely that the three parties will be found liable in tort to the manufacturing company and it is unlikely that any one party will be assigned 100% liability. It is also likely that the engineering firm and contractor will held to greater liability than the architect. The architect may also have a clause in his or her contract limiting liability and the contractor is likely to have a separate contract with the manufacturing company and that, too, may have a clause limiting liability.

Reference: Dominion Chain Co. Ltd. v. Eastern Construction Co. Ltd. et al., Marston, pp.39-42 and pp.175-177.

Case 11

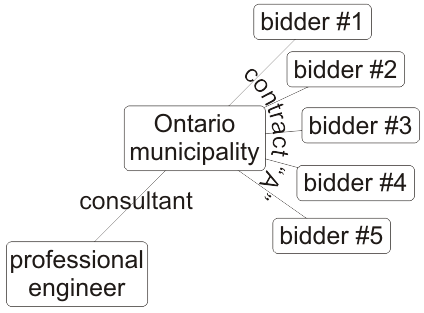

An Ontario municipality (the "Owner") decided to update and expand its water treatment facilities. To do so, the Owner invited competitive tenders from contractors for the construction of the new water treatment facility.

The Owner's consultant on the project designed the facility and prepared the Tender Documents to be given to potential contractors interested in bidding on the project. The Tender Documents included the Plans and Specifications, the Tendering Instructions which described the tendering procedure and other requirements to be followed by the bidders, the Tender Form to be completed by the bidders, the form of written Contract that the successful contractor would be required to sign after being awarded the contract, and a number of other documents.

According to the Tendering Instructions, each tenders bid was to remain "firm and irrevocable and open for acceptance by the Owner for a period of sixty days following the last day for submitting tenders". The Tendering Instructions also provided that each bidder was to include with its tender a certified cheque for $200 000 payable to the Owner as a tender deposit. In addition, the Tendering Instructions contained the following provisions describing the circumstances in which the Owner would be entitled to retain the tender deposit:

"The bidder guarantees that if its tender is accepted by the Owner and the Owner does not, for any reason whatsoever, receive the Contract signed by the successful bidder within seven days after the successful bidder has been presented with the Contract for signature, the Owner may retain the tender deposit for its own use and may accept any other tender." XYZ Construction Inc. ("XYZ") submitted its tender in accordance with the Tender Documents. Approximately ten minutes after the official time for submitting bids has expired, XYZ discovered that it made a clerical mistake in preparing its tender: XYZ had mistakenly copied a figure from a calculation sheet. Due to the clerical error, XYZ had omitted an amount of $800 000 from its tender price of $3 300 000. Immediately upon its discovery of the error, XYZ notified the Owner of the mistake and indicated that XYZ wished to withdraw its tender. XYZ and the Owner agreed that the clerical mistake was genuine; however, the Owner refused to permit XYZ to withdraw its tender.

Within two weeks, the Owner announced that it had awarded the contract to XYZ, who was the lowest bidder, and presented XYZ with the Contract for execution. XYZ refused to sign the Contract. As a result of XYZ's refusal, the Owner awarded the contract to the next lowest bidder for a price of $3 600 000.

What potential liabilities in contract law arise in this case? What would the Owner be entitled to claim from XYZ? How would the amount of the claim be calculated? Would the Owner be entitled to keep the tender deposit? Please provide your reasons and analysis. In doing so, explain the contractual relationships and indicate a likely outcome in this matter.

The company XYZ had entered into a tender contract, also known as "Contract A", with the engineering firm. As XYZ had entered into the contract without actual consideration, it should have been required to seal the tender to demonstrate consideration.

If the seal was placed on the tender, by the case Ron Engineering et al. v. The Queen in right of Ontario et al., this means the tender contract may be enforced and consequently, BIDCO would not be at liberty to withdraw the tender bid without breach of the tender contract, the remedy for which is specified in the tender contract as forfeiture of the deposit of $200 000.

If the bid was not sealed, no contract exists and by Belle River Community Arena Inc. v. W.J.C. Kaufmann Co. et al., no contract exists and therefore BIDCO would be entitled to withdraw.

XYZ, however, would not be liable for the difference between the next lowest bidder of $3 600 000 and its bid of $3 300 000 as the actual construction contract was never signed. Had XYZ signed and then breached the contract, it would have been liable for the difference of $300 000.

Reference: Belle River Community Arena Inc. v. W.J.C. Kaufmann Co. et al., Marston, pp.116-118.

Reference: Ron Engineering et al. v. The Queen in right of Ontario et al., Marston, pp.118-120 and Ch. 16 Tendering Issues—Contract A, pp.121-134.

Case 12

A supplier of information technology hardware, ABC Hardware ("ABC"), submitted a fixed price bid on a computer installation project for a large accounting firm. ABC's bid price of six million dollars was very low in comparison to the other bidders. In fact, three other bidders had each bid amounts in excess of nine million dollars.

The contract was awarded to the lowest bidder. The contract conditions expressly entitled the contractor to terminate the contract if the owner did not pay monthly invoices within thirty days following receipt of an invoice.

ABC commenced supplying computer hardware on the project and soon determined that it would likely suffer a major loss on the project, as it had made significant judgment errors in arriving at its bid price. ABC also learned that, in comparison with the other bidders, ABC had left three million dollars on the table.

After the fifth invoice was delivered, ABC was approached by the accounting firm for additional information and explanation of bills from an equipment parts supplier, the cost of which comprised a portion of the fifth invoice amount. The accounting firm requested that the additional information be provided prior to payment of the fifth invoice being due.

Although the signed contract did not obligate ABC to obtain such additional information, a representative of ABC verbally informed the accounting firm that ABC would provide the additional information. However, AC never did so.

Thirty-one days after the fifth invoice had been received, ABC notified the accounting firm that ABC was terminating the contract as the accounting firm had defaulted in its payment obligations under the specified wording of the contract.

Was ABC entitled to terminate the contract? Explain the relevant legal principle and how it should be applied in this situation.

This is a case which has similarities to the case Owen Sound Public Library Board v. Mial Developments Ltd. et al.. ABC was approached by the accounting firm for extra information and a representative of ABC gave a verbal agreement to provide extra information before the payment was made. This agreement by ABC constituted a gratuitous promise as it was not associated with any consideration. ABC did not produce the information and therefore induced the accounting firm to breach the contract. Consequently, this is an question of equitability and it is likely that the courts would equitably estop ABC from enforcing the strict terms of the contract.

Note that because the agreement was verbal, it would be insufficient for the accounting firm to do nothing once the agreement was reached. For example, as the agreement was verbal, the precise wording would have been open to interpretation. Due diligence would have insisted that the accounting firm make inquiries with the ABC to follow up on the request for information and on the day the payment was contractually due, the firm should have sent a letter indicating that it is not providing the payment with the justification that the requested information has not yet been sent. In this case, ABC would have had the opportunity to indicate that it was reverting back to the strict interpretation before the accounting firm breached the contract in which case, the accounting firm would likely have been required (provided sufficient notice was given) pay within the contractual 31 days.

Note that had the verbal agreement to supply the information occurred before the signing of the contract and that agreement had not been included in the terms of the contract, by the parol evidence rule, the accounting firm could not use the agreement.

Case 13

An Ontario pulp and paper company ("Paperco") entered into a written equipment supply contract with a manufacturer of heat exchange and turbine equipment ("Manuco"). According to the agreement, Manuco was to design, manufacture, and deliver a heat recover steam generator for Paperco's pulp and paper mill in Ontario for a purchase price of $7.5 million. Paperco would arrange to install the equipment in its mill as part of a cogeneration system for the purpose of converting steam into electricity.

According to the agreement, Manuco was to begin manufacturing the equipment on February 1st and deliver the finished product to Paperco on or before March 30th of the following year. The agreement provided that Paperco would pay the $7.5 million purchase price in monthly installments over the manufacturing period. The agreement contained the following provision:

Each installment of the purchase price shall be due and payable by Paperco on the last day of the month for which the installment is to be made. If Paperco fails to pay any installment within 10 days after such installment becomes due, Manuco shall be entitled to stop performing its work under this contract or terminate this contract."

As work progressed, Manuco invoiced Paperco for each monthly installment. Although Paperco paid the first installment on time, it was more than 20 days late in paying each of the second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth installments. Manuco never once complained about the late payments, even when Paperco apologized for the delayed payments and commented in a meeting with Manuco that Paperco's current cash flow difficulties were the reasons for the late payments. Manuco even commented at three separate meetings, in response to Paperco's acknowledgment of its cash flow difficulties, that it understood that Paperco had cash flow problems and that Manuco was prepared to wait for the late payments provided the payments weren't more than 30 days late.

By the middle of September, it became apparent to Manuco that due to serious cost overruns resulting from its own design errors and lack of productivity, it would stand to lose a substantial amount of money on the contract by the time the equipment would be completed. Although the installment for August had been invoiced and was due on August 31st, Paperco had not paid it by September 15th. On September 15th, Manuco terminated the contract.

Was Manuco entitled to terminate the contract? Identify the contract law principles that each of Paperco and Manuco may argue should apply and explain the basis of the principles of how they should apply.

This is a case which is very similar to the case John Burrows Ltd. v. Subsurface Surveys Ltd. et al.. Manuco had developed a pattern allowing Paperco to breach the term in the contract whereby Paperco was able to delay payment by more than twenty days from the dates specified in the contract. In addition, the representatives of Manuco appear to have made a gratuitous promise (an agreement made without consideration) to wait for late payments provided the payments were not more than 30 days late. Consequently, while courts will (by the parol evidence rule) not consider agreements made before the signing of the contract but which where not written into the contract will; they will will consider both actions and verbal agreements when there is a question of equitability.

Therefore, having established a pattern Manuco of sanctioning the same breach of contract, Manuco would likely be equitably estopped from simply revert back to the strict terms of the contract.

Case 14

A joint venture consisting of both engineering and contracting firms entered into a contract with an Ontario city to design and build an all-electronic toll highway expressway featuring both underground tunnel portions and surface portions of the highway. The contract also required the joint venture to design, install, and implement an electronic tolling system to accommodate specified numbers of vehicles, all as specified in the request for proposal for the design and construction of the expressway, as published by the city.

The contract between the city and the joint venture provided that the expressway was to be fully operational by the specified date, failing which the joint venture contractor would be responsible to pay to the city liquidated damages (based on lost toll revenues in accordance with the project's feasibility study and financial plan) of $300 000 for each day beyond the specified completion date until the expressway and its all-electronic tolling technology was finally installed and fully operational. The contract also included a provision limiting the contractor's liability for liquidated damages under the contract to the maximum amount of $30 000 000.

With the city's approval, the joint venture contractor then subcontracted to a firm specializing in tolling technology the obligations to design, install, and implement the tolling technology system as required by the city's specifications. The subcontract contained a provision obligating the tolling technology to be responsible to the joint venture contractor to provide a fully operational tolling system by the same specified date and for the same $300 000 of daily liquidated damages (subject to the the same maximum amount of $30 000 000 in liquidated damages) as set out in the joint venture contract between the joint venture contractor and the city.

Although the expressway was otherwise operational by the specified completion date, the tolling technology subcontractor experienced difficulties in completing the installation and implementation of the tolling technologies in accordance with the requirements of the subcontract. In fact, the tolling technology subcontractor was 120 days late in successfully completing the design, installation, and implementation of the tolling technology system as required by the subcontract (and the contract).

Explain and discuss what claim the joint venture contractor could make against the tolling technology subcontractor in the circumstances. In answering, explain the approach taken by Canadian courts with respect to contracts that limit liability and include a brief summary of the development of relevant case precedents.

The liquidated damages written into the contract are substantiated by actual projected damages perceived at the time of the signing of the contract and are therefore legal and the courts would likely enforce that provision of the term.

The sub-contractor was 120 days late and therefore the liquidated damages would amount to $300 000 days × 120 days = $36 000 000. The maximum liability, however, is $30 000 000 and therefore the sub-contractor would be liable for the lesser amount.

Relevant case law includes the concept of fundamental breach with Harbutt's Plasticine Ltd. v. Wayne Tank and Pump Co. Ltd. where the defendant used "thoroughly" and "wholly" unsuitable for is purpose. The concept of fundamental breach has not been overruled; however, in the case of Hunter Engineering Company Inc. v. Syncrude Canada Ltd., the decision was to accept the freedom of contract and true "construction approach". In this case, the tolling technology was ultimately made operational and it would be exceptionally unlikely that the concept of a fundamental breach would be applicable here.

New: In Tercon Contractors Ltd. v. The Queen in right of British Columbia, the Supreme Court of Canada stated that "With respect to the appropriate framework of analysis the doctrine of fundamental breach should be 'laid to rest'."

Another question is the scope of the project: the plaintiff has a duty to mitigate and while the size of the project is not given, 120 days appears to be an exceptionally long period of time and the actions of both the city and the contractor may be taken into account.

Another consideration which must be taken into account are any actions or inactions on the part of either the city or the contractor which may have induced the sub-contractor to default on the contract from the case Owen Sound Public Library Board v. Mial Developments Ltd. et al.

Assuming that the contractor did take appropriate steps to mitigate the damage and there was no induction by either the city or the contractor to default, the subcontractor would likely be liable for $30 000 000.

Case 15

Live Rail Inc. ("Live Rail"), a company specializing in the manufacture and installation of railway commuter systems was awarded a contract by a municipal government to design and build a transit facility in British Columbia. The contract specified electrically powered locomotives. As part of the design, Live Rail was contractually obligated to design an overhead contact system in a tunnel. Live Rail subcontracted the subdesign of the overhead contact system to a consulting design firm, Ever Works, Ltd. ("Ever Works").

Ever Works designed an overhead contact system in the tunnel; however, in doing so it did not carry out any testing nor did it gather any data of its own relating to the conditions inside the tunnel. It did not even request copies of the underlying reports which, had they been examined, would have indicated that there was a large volume of water percolating through the tunnel rock and that the tunnel rock contained substantial amounts of sulphur compounds. The project documentation that was turned over to Ever Works by Live Rail did not include the underlying reports, but did identify the existence and availability of the underlying reports.

The construction of the rail system through the tunnel was completed in accordance with the Ever Works's design. However, within eight months of completion, the overhead contact system in the tunnel became severely corroded and damaged due to the water seepage in the tunnel.

As a result of the corrosion damage, the municipality had to spend substantial additional money on redesigning and rewiring the system.

What potential liabilities in tort law arise in this case? In your answer, explain what principles of tort law are relevant and how each applies to the case. Indicate the likely outcome to the matter.

This case is very similar to that of B.C. Rail Ltd. v. Canadian Pacific Consulting Services Ltd. et al. (which brings into question the disclaimer "Any similarity in the questions to actual persons or circumstances is coincidental.")

In the case of B.C. Rail v. CP Consulting, the contract had a provision that reasonable skill, care and diligence must be made in providing the services.

In the B.C. Rail v. CP Consulting, the plaintiff sought damages for both breach of contract and for negligence (a liability in tort). For liability in tort, one must demonstrate that

- the defendant owed the plaintiff a duty of care,

- the defendant breached that duty by his or her conduct, and

- the defendant's conduct caused the injury to the plaintiff.

The purpose of tort law is to compensate the injured party for the damages and not to punish the tortfeasor.

Reference: Marston, p.39.

While Ever Works has no contract with the municipal government, as it is being paid in the scope of a larger project, it has a duty of care to the government.

In this case, as the work being done by Ever Works falls under the practice of professional engineering, had this occurred in Ontario, the company would have required a Certificate of Authorization and a professional engineer to supervise and take responsibility for the work. As a professional engineer, he is required to not be negligent in providing services and it would appear that by not requesting testing, collecting data, nor requesting the underlying reports, Ever Works is vicariously liable for the negligent actions of the professional engineers. While British Columbia may have variations on such requirements, it is almost certain that Ever Works has a professional engineer who is in some ways responsible for the service and that the service actually performed constituted negligence and some form of professional misconduct.

By acting negligently and by vicarious liability, the defendant therefore breached the duty of care owed to the municipal government.

The municipality is therefore likely to be entitled to recover costs for redesigning and rewiring the overhead contact system.

In this case, Ever Works is concurrently liable in tort to the municipality and in contract to Live Rail Inc.

Light Rail had a responsibility to ensure that the work of the sub-contractor was reasonable and it appears to have failed in that case, too. For example, Light Rail should likely have provided the documents with the contract and should have also inspected the progress of Ever Works. Consequently, Light Rail is concurrently liable to the municipality in both contract and tort.

As both Light Rail and Ever Works are liable in tort to the municipality, they are considered to be concurrent tortfeasors and given the details of this case, it is unlikely that either one would be assigned 100% responsibility in tort.

Case 16

An owner/developer (the "owner") entered into a contract with an architectural firm (the "architect") for design and contract administration services in connection with the construction of a ten-storey commercial office building.

The building was designed to be entirely surrounded by a paved podium concrete deck used for parking and driving, and the design provided for a parking area below the deck. The podium deck was divided by construction joints and expansion joints placed to allow thermal expansion of the concrete as the temperature changed. The land on which the building was located sloped towards a river so the lower parking deck was designed to be partially open to the outside.

The architect engaged a structural engineering firm (the "engineer") as the architect's sub-consultant on the project. The engineering firm, in its agreement with the architect, accepted responsibility for all structural aspects of the construction, and also specifically acknowledged responsibility for the design of the paved podium concrete deck and the parking area below.

Upon completion of the design and the tendering process, the owner entered into a contract for the construction of the project with an experienced contractor who had submitted the lowest bid.

Unfortunately, within tow years following construction, a significant number of leaks occurred in the podium deck which resulted in water leaks in the lower parking garage.

The contract specifications had called for a specific rubberized membrane to be installed for the purpose of waterproofing the podium deck. However, during construction, at the suggestion of the roofing subcontractor and without the knowledge of the owner, another asphalt membrane product was substituted for the rubberized membrane product specified. Neither the engineer nor the architect objected to the substitution when it was suggested. The roofing subcontractor had suggested the substitute membrane because it was more readily available and would speed completion of construction. The design engineer and the architect took the position that they would rely on the subcontractor's recommendation.

During the investigation into the cause of the leaks, another structural engineering firm provided its opinion that the rubberized membrane as specified in the contract was a superior product to the substituted membrane; that the substituted membrane was brittle and could fracture or crack under certain circumstances, particularly on podium decks with expansion joints; that the winter temperatures had contributed to the breakdown of the substitute membrane as it became more brittle at colder temperatures; and that the substitute membrane should not have been used over expansion joints on a dynamic surface podium deck. The second engineering firm also expressed the opinion that the designers ought to have taken into account the non-static nature of the deck that featured these expansion joints and should not have accepted the substitute membrane.

Ultimately, to remedy the leaks, the substitute membrane had to be replaced by the rubberized membrane originally specified in the contract.

What potential liabilities in tort law arise in this case? In your answer, explain what principles of tort law are relevant and how each applies to the case.

To demonstrate liability in tort, one must demonstrate that

- the defendant owed the plaintiff a duty of care,

- the defendant breached that duty by his or her conduct, and

- the defendant's conduct caused the injury to the plaintiff.

The purpose of tort law is to compensate the injured party for the damages and not to punish the tortfeasor.

Reference: Marston, p.39.

In this case, we have the unintentional tort of negligence where the conduct of individuals falls short of what a reasonable person would do protect an individual from foreseeable risks. The tort of negligence was precedent by the case Donoghue v. Stevenson. In this case, the subcontractor who should have known the properties of the materials he was working with and therefore should have anticipated that the asphalt membrane was not an appropriate replacement when compared to the rubberized membrane and therefore was negligent in his suggestion. The contractor with whom the owner entered into a contract may be liable both in tort and in contract for an experienced contractor should have also been aware of the differences. The architect and engineer both accepted the recommendation apparently without determining the validity of the statements made by the contractor. Thus, this case would have four concurrent tortfeasors.

The purpose of tort law is to compensate the injured party and is not meant to penalize the tortfeasors. The courts would likely award the the owner/plaintiff the costs of replacing the asphalt membranes with the original rubberized membranes and the fees would be distributed by the courts based on the perceived level of negligence.

Reference: Marston, p.39.

Case 17

A $30 000 000 contract for the design, supply, and installation of a cogeneration facility was entered into between a pulp and paper company ("Pulpco") and an industrial contractor. The cogeneration facility, the major components of which included a gas turbine, a heat recovery steam generator, and a steam turbine, was to be designed and constructed to simultaneously generate both electricity and steam for use by Pulpco in its operations.

The contract provided that the electrical power generated by the cogeneration facility was not to be less than 25 MW. A liquidated damages provision was included in the contract specifying a pre-estimated amount payable by the contractor to Pulpco for each megawatt of electrical power generated less than the minimum 25 MW specified. Other provisions specified additional liquidated damages at prescribed rates relating to other matters under the contract, including any failure by the contractor to meet the required heat rates or to achieve completion of the facility for commercial use by a stipulated date. However, the contract also included a maximum liability provision that limited to $5 000 000 the contractor's liability for all liquidated damages due to failure to achieve (i) the specified electrical power output, (ii) the guaranteed heat rate, and (iii) the specified completion date. The contract clearly provided that under no circumstances was the contractor to be liable for any other damages beyond the overall total of $5 000 000 for liquidated damages. Pulpco's sole and exclusive remedy for damages under the contract was strictly limited to total liquidated damages, up to the maximum of $5 000 000. The contract specified that Pulpco was not entitled to make any other claims for damages, whether on account of any direct, indirect, special or consequential damages, howsoever caused.

Unfortunately the contractor's installation fell far short of the electrical power generation specifications (achieving less than 25% of the specified megawatts) and the heat rates specifications provided in the contract. The contractor was paid $27 000 000 before the problems were identified on start-up and testing. Because of its very poor performance, the contractor also failed to meet the completion date by a very substantial margin. Applying the liquidated damages provisions, the contractor's overall liability for all liquidated damages under the contract totaled $4 000 000. Ultimately, Pulpco had to make arrangements through another contractor for new equipment items and parts to be ordered and installed in order to enable the cogeneration facility to meet the technical specifications, with the result that the total cost of the replacement equipment and parts reached an additional $15 000 000 beyond the original contract price of $30 000 000.

Explain and discuss what claim Pulpco could make against the contractor in the circumstances. In answering, explain the approach taken by Canadian courts with respect to contracts that limit liability and include a brief summary of the development of relevant case precedents.

The industrial contractor entered into a contract with Pulpco whereby the cogeneration facility to be built was to produce no less than 25 MW. In reality, the power generated was less than 25% of the specified power.

The industrial contractor had limited its liability to $5 000 000 contract and this strictly for any liquidated damages; however, the liquidated damages totaled to only $4 000 000 while the additional expenses included $15 000 000 over and above the expected cost of $30 000 000.

Relevant case law includes the concept of fundamental breach with Harbutt's Plasticine Ltd. v. Wayne Tank and Pump Co. Ltd. where the defendant used "thoroughly" and "wholly" unsuitable for is purpose. The concept of fundamental breach has not been overruled; however, in the case of Hunter Engineering Company Inc. v. Syncrude Canada Ltd., the decision was to accept the freedom of contract and true "construction approach". In this case, the cogenerator facility did operate even if only at 25% efficiency and therefore would be unlikely that the concept of a fundamental breach would be applicable here and therefore the limitation of liability would likely be upheld by the courts and while the industrial contractor would be responsible for the $4 000 000 in liquidated damages, the firm Pulpco would be liable for the balance of $11 000 000.

Case 18

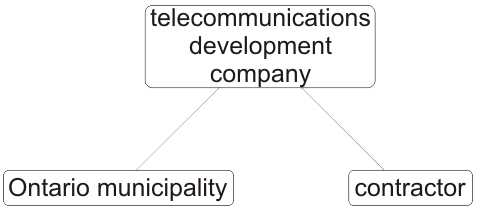

A telecommunications development company leased an outdated and unused underground pipe system from an Ontario municipality. The developer's purpose in leasing the pipe was to utilize it as an existing conduit system in which to install a fibre optic cable system to be designed, constructed and operated in the municipality by the telecommunications developer during the term of the lease. All necessary approvals from regulatory authorities were obtained with respect to the proposed telecommunications network.

The telecommunications development company then entered into an installation contract with a contractor. For the contract price of $4 000 000, the contractor undertook to complete the installation of the cable by a specified completion date. The contract specified that time was of the essence and that the contract was to be completed by the specified completion date, failing which the contractor would be responsible for liquidated damages in the amount of $50 000 per day for each day that elapsed between the specified completion date and the subsequent actual completion date. The contract also contained a provision limiting the contractor's maximum liability for liquidated damages and for any other claim for damages under the contract to the maximum amount of $1 000 000.

Due to its failure to properly staff and organize its workforce, the contractor failed to meet the specified completion date. In addition, during the installation, the contractor's inexperienced workers damaged significant amounts of the fibre optic cable, with the result that the telecommunications development company, on subsequently discovering the damage, incurred substantial additional expense in engaging another contractor to replace the damaged cable. Ultimately, the cost of supplying and installing the replacement cable plus the amount of liquidated damages for which the original contractor was responsible because of its failure to meet the specified completion date, totaled $1 800 000.

Explain and discuss what claim the telecommunications development company could make against the contractor in the circumstances. In answering, explain the approach taken by Canadian courts with respect to contracts that limit liability and include a brief summary of the development of relevant case precedents.

The liquidated damages written into the contract are likely substantiated by losses in profits anticipated at the time of the signing of the contract and are therefore legal and the courts would likely enforce that provision of the term.

The contractor was both responsible for the delays and additional damage to the amount of $1 800 000; however, as the maximum liability is $1 000 000, this is the most that the telecommunications development company could hope to recuperate.

Relevant case law includes the concept of fundamental breach with Harbutt's Plasticine Ltd. v. Wayne Tank and Pump Co. Ltd. where the defendant used "thoroughly" and "wholly" unsuitable for is purpose. The concept of fundamental breach has not been overruled; however, in the case of Hunter Engineering Company Inc. v. Syncrude Canada Ltd., the decision was to accept the freedom of contract and true "construction approach". In this case, the work was not wholly unsuitable as the cost of replacement was less than half the cost of the original contract and it would be exceptionally unlikely that the concept of a fundamental breach would be applicable here.

In this case, the telecommunications development company would be liable for the balance of $800 000.

Case 19

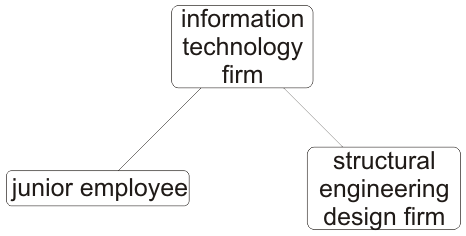

An information technology firm assigned to one of its junior employee engineers the task of developing special software for application on major bridge designs. The employee engineer had recently become a professional engineer and was chosen for the task because of the engineer's background in both the construction and the software engineering industries.

The firm's bridge software package was purchased and used by a structural engineering design firm on a major bridge design project on which it had been engaged by contract with a municipal government.

Unfortunately, the bridge collapsed in less than one year after completion of construction. Motorists were killed and injured.